63rd THESSALONIKI INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

3-13/11/2022

Indigenous Cinema

Τhe Festival’s grand tribute breaks the rules

From Canada’s Inuit and the Latin American tribes all the way to the Australian Aboriginals and New Zealand’s Māori people, the 63rd Thessaloniki International Film Festival sheds light onto cultures, ways of life, and worldviews that have been ostracized from the official frame of our definition of the world, through a large-scale tribute to indigenous cinema.

TIFF is one of the first film festivals to host a grand tribute to indigenous cinema, featuring 17 fiction films. Either shot by indigenous directors or placing the lives of the indigenous people on the spotlight, the tribute’s 13 full-length and 4 short films stand up against the stereotypical depiction of the colonial glance and the “exoticism” of the Western gaze. Moreover, great value lies in the fact that many of the films were shot in languages and dialects driven to the boundary of extinction.

The visibility and the outwardness of indigenous cinema pave the way for an invaluable cultural re-appropriation, through which indigenous people reshape their own representation, claiming the right to be the ones to define the images that form their identity. The reach of TIFF’s tribute extends way beyond cinema and art, going as far as the unseen aspects, the origins and the rich gamut of life and our world, which are constantly under threat and attack.

Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (USA, 1961) revolves around a group of young indigenous Americans, living in LA’s Bunker Hill. Yvonne, a pregnant Apache woman, and Homer, her Hualapai husband, share their tiny flat with Tony, a gifted Mexican, and four native women. At night, when men go out on a drinking, gambling and flirting spree, Yvonne goes to the movies all by herself or roams in the streets, oozing a repressed yearning. The film’s documentary-like black and white frames capture fragments of the life in the metropolis, depicting snapshots from a dislocated generation, torn between its origins and the bleak everyday life of the contemporary urban landscape.

Barry Barclay’s Ngāti (New Zealand, 1987) is the first full-length fiction film to be directed and written by a Māori filmmaker. The movie portrays the post-colonial New Zealand of the 40s, where the harmonious coexistence between the white and the indigenous population is still a distant illusion. A young Australian doctor arrives in a coastal village to seek for his roots. As the locals warmly welcome him, he becomes impressed by the way they stick together, as the village’s factory is about to shut down, threatening to plunge the entire region into decay. Initially seeing himself as a mentor, he quickly realizes that he is the one to learn from the natives’ traditions, way of thinking and sense of community. This low-key and gripping story of a man who is in search of his identity stands as a landmark in the history of indigenous cinema.

Visual and multimedia artist, photographer and director Tracey Moffatt is the most influential and multifaceted voice in the Aboriginal art world, whose works and exhibitions have been showcased in institutions such as Tate and MOCA. In BeDevil (Australia, 1993), three stories unfold on the two-fold axis of the otherworldly and the Australian tradition. Rick, an Aboriginal boy living near a swamp, is haunted by the image of an American soldier who drowned in quicksand. Ruby and her family live in a house next to long-abandoned railway lines, where ghostly apparitions are to be seen all the time. A landlord is having trouble evicting the tenants of an old warehouse - a couple that has been dead for years. Reality, colonial past, historical traumas, legends and folklore tales are interweaved in a mystical and hallucinatory movie.

Seven Songs of the Tundra (Finland, 2000) by Anastasia Lapsui and Markku Lehmuskallio takes place amidst the infinite white tundra, where a small religious cult sacrifices a reindeer. A ceremonial song accompanies the sacrifice, triggering a narrative divided in seven chapters, which re-enacts a pivotal point in the Nenets natives’ history. Deprived of their independence and prosperity, the nomadic reindeer breeders were ostracized from their homeland and asked to abandon not only their language and traditions, but also their children that were forced to enrol to boarding schools. Bordering in the threshold between documentary and fiction, the first movie ever to be shot in the Nenets language is a touching drama that explores the deep wounds inflicted by the loss of identity and the struggle for survival.

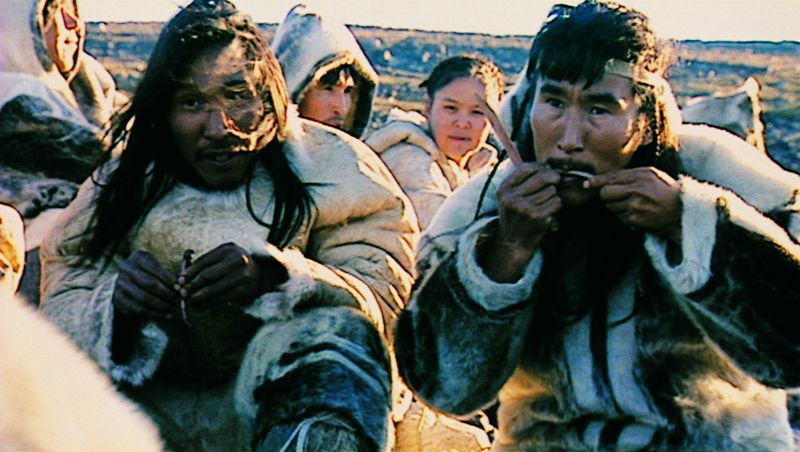

Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (Canada, 2001) by Zacharias Kunuk is the first full-length fiction film to be directed and written by an Inuit filmmaker. In addition, it is the first ever film to be shot in the Inuktitut language. The plot is set in the North-eastern Arctic, long before the region’s first contact with the Europeans, drawing inspiration from a traditional Inuit’s folk tale. Shot in the tiny island of Igloolik over a period of six months, Atanarjuat was one of the first films to be made entirely on HD video. Making use of natural light for the most part, Kunuk and his cinematographer, Norman Cohn, capture images, colour hues and tonalities that introduce to us a new and unexplored world. The movie snatched the Camera d’Or award for best debut film in the Cannes Film Festival, also bearing the title of “the greatest Canadian film of all times”, as voted in a poll conducted by Toronto International Film Festival.

Birdwatchers (Brazil-Italy, 2008) by Marco Bechis takes us to Brazil’s Mato Grosso do Sul, where landowners live in wealth, spending time with the birdwatching tourists who flood the area. In the meanwhile, at a hand’s distance, the natives’ turmoil is on the rise. Exiled in reservation camps, with no other prospect than to work as modern-day slaves in the sugar cane plantations, many natives are driven to suicide. One such incident ignites the spark of the rebellion, when a group of Guarani-Kaiowá natives camps right outside a mansion, claiming what is rightfully theirs. However, and apart from the animosity and the hatred, the two opposed sides are intrigued by the “otherness” that stands on the other side of the fence. This feeling of curiosity will trigger a profound bond between a young Shaman apprentice and the daughter of a landowner.

Warwick Thornton’s Samson & Delilah (Australia, 2009) showcases a sensitive and unconventional love story between two teenager Aboriginals, in the desert of Australia’s inner land, who embark on a survival journey full of hardships. Their tacit but eloquent in meanings odyssey reflects the fragile nature of youth, striving to survive in an environment governed by violent marginalization, lack of prospect and discriminations. Through scarce dialogues, the resourceful use of expressive means and the spot-on guidance of the amateur cast, the director weaves an unrefined and rough love story that is at once humane and tender.

Heart of Time (Mexico, 2009) by Alberto Cortés permeates the uncharted territory of Chiapas state, in Mexico, in the core of the Zapatistas’ struggle for autonomy. Sonia is about to get married, the families of the couple-to-be have settled all the details, the dowry -in the form of a cow- has been agreed upon. However, Sonia is in love with someone else, a fighter of the guerrilla army. EZLN is now bound to object to the wedding; the entire community is seeking ways to resolve the matter, asking for its voice to be heard, with the hope that love will overcome repression.

Shot entirely in Samoa’s tiny island of Upolu and filmed in the local language, The Orator (Samoa-New Zealand, 2011) by Tusi Tamasese builds a heart-wrenching drama that speaks of courage, forgiveness and love. Our main hero, Saili, lives a simple and humble life with his beloved wife and their daughter, in a secluded traditional village. Forced by the circumstances to protect his land and family, Saili must overcome his fears and find the courage to defend the people he loves.

The Quispe Girls by Sebastián Sepúlveda take us to the dry and arid Atacama Plateau, in Chile. Isolated from the rest of the world, sisters Justa, Lucía and Luciana are devoted to their goat herd. Nevertheless, they are tormented by loneliness, feeling obliged to repress their femininity in order to survive. The news that dictator Pinochet has prohibited herding in the area becomes the turning point in their silent struggle to preserve their way of life. The three sisters collapse in the face of this imminent threat, and all alternatives seem equally gloomy. The landscape’s infinity, as well as the emotional detachment of the dialogues, enhance the matter-of-fact ambiance of a directorial debut that draws inspiration from real events.

In the ice-cold Patagonia desert, living conditions are rough, as portrayed in Gerónima, a landmark film in Latinamerican cinema. The titular female hero is unable to offer safety to her four little children, but at least she manages to make ends meet, taking life as it comes and facing hardships with perseverance. When a state health official decides to intervene so as to “improve” the family’s quality of life, he fully implements the racist policies of the 70s – during the dictatorship and throughout the “Dirty War.” The entire family (of Mapuche origins) is uprooted and transferred to a public hospital. In this new environment, Gerónima feels unwanted and struggles to avoid a breakdown. The original recording of Gerónima’s clinical diagnosis is heard as a background narrative, firmly documenting the atrocious historical events that inspired the script.

Tanna (Australia, 2015) takes us to a tiny little island of Vanuatu, where different ways of life are caught up in conflict: Some residents have converted to the Christian religion, while others remain faithful to ancestral traditions. As her adulthood initiation ceremony is closing in, a young girl decides to run off with the grandson of a neighboring tribe’s chief. Aware that endogamy is frowned upon by tradition, as inter-tribal marriages help to ensure peace, the two young lovers are trying to conceal their relationship from everyone. Based on true events that took place in the 1980s, and entirely shot in the Nauvhal language, Tanna was a Best Foreign-Language Film Oscar nominee.

Sami Blood (Sweden-Denmark-Norway, 2016) by Amanda Kernell is a heartfelt tribute to those left behind, but also to those who chose to flee from a community living on the brink of the world. At once, it is an alternative-personal view on the colonial past of a “civilized” country, as seen through the eyes of a teenage girl. Elle-Marja, from the reindeer-breeding Sami indigenous tribe, is a 14-year-old boarding school student. Racism was formally grounded in the 30s, and Elle is submitted to bio tests that “measure” when and if a native is entitled to integrate to an all-whites society. Elle is dreaming of a different life, but to make her dreams come true she must become someone else and break off all ties with her family and culture.

Short films:

In the acclaimed The Ballad of Crowfoot (Canada, 1968) by Willie Dunn, a dynamic editing juxtaposes archival photos with Dunn’s ballad. This heart-wrenching and painful mix of music and image unfolds the story of both Canada’s indigenous people and Crowfoot, the legendary chief of the Blackfeet tribe.

In When All the Leaves Are Gone (Canada, 2010) by Alanis Obomsawin, the main protagonist is the only native student in an all-whites school, in the 40s. The obvious animosity against the 8-year-old girl will escalate to open abuse following the reading of an excerpt in class that describes all indigenous people as savages and barbarians. All alone in her ordeal, she finds comfort and strength in the sheltered world of her magical dreams. Inspired by events experienced in real life by the director and screenwriter of the film, When All the Leaves Are Gone intertwines autobiographical elements, fiction and local legends to weave a moving story about resilience and the redeeming power of imagination.

Snow in Paradise (Νew Zealand, 2011) by Justine Simei-Barton and Nikki Si’ulera takes place in the idyllic and colourful Aitutaki of the Cook Islands, where two young siblings spend their days catching fish, opening up coconuts and peeling fruit for their grandmother. Life on this earthly heaven is serene, but not for long. From 1966 to 1996, 188 nuclear tests were carried out in the South Pacific atoll of Mururoa. No-one took the trouble of warning the neighbouring islands’ population and any talk on the horrendous repercussions has been hushed ever since.

In Blackbird (Australia, 2015) by Amie Batalibasi, taking place in the end of the 19th century, two siblings are forced to move to Australia and work as modern-day slaves in a sugar plantation, after being displaced from their homeland, the Solomon Islands. Perching between the memories from home and the unbearable reality of the uprooting, the camera juxtaposes images from lush landscapes and the monotony of the fields and everyday labour. Shedding light onto one of the darkest and most silenced pages of Australian history, the country’s “sugar slaves”, this lyric short film stands as a declaration of determination and desire to survive.