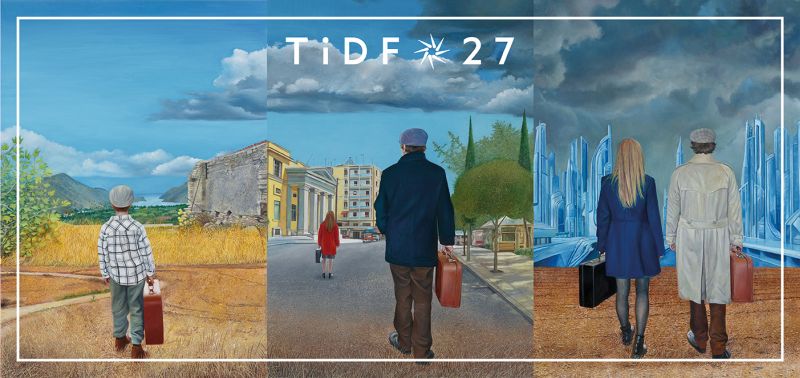

27th THESSALONIKI INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL // 6-16/03/2025

Geography of the Gaze: Off-Plan Greece (1950-2000)

A grand tribute on the occasion of the discovery of Kastoria directed by Takis Kanellopoulos

The 27th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival (March 6-16, 2025) invites us to embark on a unique cinematic journey in the Greek countryside through documentaries of renowned filmmakers, most of them rare and off the radar. On the occasion of the recent discovery of the documentary Kastoria (1969) directed by Takis Kanellopoulos, a film considered lost up until now, the tribute titled Geography of the Gaze: Off-Plan Greece (1950-2000) lines up 19 documentary films that compose a multifaceted and illuminating portrait of the social, political and cultural life of Greece in the second half of the 20th century.

This first spark for this thrilling adventure was ignited during the preparations for the 64th Thessaloniki International Film Festival (November 2024). Within the framework of the large-scale tribute to Takis Kanellopoulos, the Festival searched for Kastoria, but to no avail. Nevertheless, through this initial quest the research was carried on, eventually leading to the discovery of the film in 2024, through a network of collectors. This remarkable finding will be screened at the 27th TiDF, along with the documentaries Thasos and Macedonian Wedding that jointly make up the informal “Macedonian Trilogy” of documentaries directed by Takis Kanellopoulos.

With Kastoria as the starting-off point, the Festival attempts to “map” the Greek countryside through a series of documentaries directed by iconic Greek filmmakers, which explore the spirit, the collective memory and the human geography of the Greek land. The tribute’s films approach with resourceful and pervasive ways certain key notions such as tradition, personal experience, trauma and coexistence. A number of the tribute’s documentaries have been sparsely screened on the big screen and constitute invaluable treasures not only for Greek film history, but also for the country’s cultural heritage. The tribute’s curators are: Eleni Androutsopoulou, head of the Festival’s Greek Program, Manolis Kranakis, film critic, and Yannis Palavos, from the Festival’s International Program.

On Saturday March 8th, at 13:00, an open discussion will be held at Pavlos Zannas theater, under the title “Kastoria: The Rediscovered Land of Takis Kanellopoulos”. The tribute’s curators will unravel the thread of the adventurous discovery of the film, linking it with the core question raised by the tribute: How is the psyche of a particular topos, and in particular that of the Greek country, inscribed and reflected through the singular gaze of prolific Greek filmmakers?

In addition, the Festival is hosting once again its time-honored universally accessible screenings thanks to the support of Alpha Bank, the Festival’s Accessibility Sponsor. In particular, the audience will have the rare opportunity to watch two exquisite documentaries, included in the tribute’s program and directed by the dearly departed Takis Hatzopoulos. The unforgettable Greek filmmaker, who left a rich and erudite work behind, was a key factor, alongside Lakis Papastathis, for the overall rebirth and rejuvenation of Greek documentary. The duo co-founded the production company Cinetic, introducing to the Greek audience one of the most successful and long-lived programs in the history of Greek television, legendary Paraskinio (1976-2013). The full-length documentary Gazoros Serron (1974), bestowed with the Best Production Award at the 15th Thessaloniki Film Festival, which unveils the genuine spirit and identity of the Greek countryside, as well the short documentary Prespes (1966), awarded at the 7th Festival of Greek Cinema as the Best Short Documentary Film, will be screened with universally accessible terms at the 27th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival. The two films will be screened with Audio Description for the blind and the visually impaired, as well as with Subtitles for the Deaf of Hard of Hearing both in physical spaces and online.

Let’s take a look at the tribute’s films:

Leucada, the Island of the Poets, Roviros Manthoulis, 1958, 16΄

“For Leucada has no beginning, and no end…” Considered the first creative documentary in Greek cinematic history, this short homage shot by Roviros Manthoulis as his debut film on the island of Lefkada in 1958, commissioned by the Hellenic Press Office, is nothing short of a voyage through a land that takes the poetry of everyday life as its guide, since every image – be it sweeping or small – of this stunningly beautiful island is “translated” via the voice-over into a story forged from many ages of myths and traditions. Impressionistic in its gaze, lyrical in its word, poetic in its references to the celebrated local bards Aristotelis Valaoritis and Angelos Sikelianos, and with Manthoulis clearly intent on capturing the very sensations of this isle, Leucada: The Island of the Poets bears something of the innocence and grandeur of an era that is no more. Meanwhile, as a work of documentary, it remains invaluable too across the decades as a historical record harking back to the beginnings of a documentary approach that slips free from matter-of-fact information and attempts instead to touch upon something deeper within the heartlands of people and places; one that also harks back to a rare cinematic reminiscence of a Greek summer devoid of tourists.

Firewalkers of Greece, Roussos Koundouros, 1959, 10΄

In what is considered the most emblematic example of his pioneering approach to blending ethnography with scientific documentation, Roussos Koundouros entrusts the words of Nikos Gatsos to guide us – both as witnesses and as participants – through a nearly metaphysical tradition dating back to antiquity: that of firewalking. A “strange ritual” that the Anastenarides of Eastern Thrace carried with them across Macedonia – from Serres to Veria, from Drama to Thessaloniki. The bizarre, frenzied, Dionysian dance of the Anastenarides becomes the beating heart of a rigorously structured, ritualistic narrative. The film interweaves population movements, sacred icons of Saints Constantine and Helen, animal sacrifices, drums that seem to play by themselves, and bare feet stepping onto burning embers – heated to 500 degrees Celsius – without suffering pain or burns. In the few minutes of its duration, the film pieces together a Greece that still believes in miracles. More than just a documentation of an ancient custom, Firewalkers of Greece also captures the resilience of people who, in their moments of trance, touch something divine – the very God to whom they dedicate themselves. The film was screened at the Karlovy Vary and Florence Film Festivals, as well as at the First Week of Greek Cinema in Thessaloniki in 1960, where Roussos Koundouros was honored by the jury for his invaluable contribution to the field of documentary filmmaking.

Macedonian Wedding, Takis Kanellopoulos, 1960, 23΄

“For unto us a director is born” raved the Greek press after Macedonian Wedding first screened in 1960. And rightly so, for this short documentary that anointed the 27-year-old Takis Kanellopoulos as Greek cinema’s new hope overnight is a visual poem of rare sensitivity. What starts as a documentation of joyous wedding rites in an eastern Macedonian village (Velventos in Kozani) is transmuted through the director’s gaze into an elegy on the parting of ways – as if Persephone is to descend into Hades – and the chthonic, paganistic bite of the natural world. The germ of Kanellopoulos’ later work is already apparent here: the low-key tone, the lyricism, the Macedonian landscape, the charge borne by what is borderline, and the female face that so captivated him. Macedonian Wedding won Best Short Film at the First Week of Greek Cinema, and First Prize at the Belgrade Film Festival (1961).

Thasos, Takis Kanellopoulos, 1961, 18΄

“In making this short film about Thasos, we were not seeking to depict the island. We were trying to capture something of its magic and its soul.” Staying true to the ethnographic approach he had just introduced with Macedonian Wedding, Takis Kanellopoulos would, with his second short film, continue to chart that unknown Macedonian region where folkloric kitschness co-exists with its critique, nativeness with its negation, and myths with their mode of narration. In Thasos, by the humble means of a limpid and poetic observational gaze, slivers of an island life routine are made into a proposal countering the picture-postcard image of an entire country, at precisely the time when Greece was experiencing its first explosive wave of tourism back in the 1960s. Rhythmic, at times frenzied and bordering on paganistic, structured around traditional folk songs of the Greek islands, with an emphasis on seeking out a sense of familiarity with the “feel” of the island, and with humankind and the natural world set at its heart, Thasos was not screened at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival. It did, however, receive a special mention at the Moscow International Film Festival, and was presented in anthology form at special screenings in Thessaloniki and commercial screenings in Athens, in time earning itself a prominent place within Kanellopoulos’ efforts towards a modernist approach that were renegotiating – at high risk, and with unprecedented decisiveness – the notion of patridognosía [locally-rooted knowledge of one’s homeland].

Aluminium of Greece, Roussos Koundouros, 1965, 18΄

Documenting the entire cycle of aluminium production, from bauxite extraction to final processing, and capturing the construction of the industrial infrastructure at Aspropyrgos, Boeotia, in 1960, Roussos Koundouros delivers Aluminium of Greece – one of the first industrial documentaries in Greek cinema, a striking testament to his scientific precision and cinematic vision in recording the radical transformation of the Greek landscape. With no voice-over narration, but guided by Tania Karali’s pioneering electronic score, Koundouros doesn’t simply depict the before and after of an industrial process. In full harmony with his artistic ethos – and almost in defiance of the film’s corporate commission by “Aluminium of Greece” – he challenges the limits of cinematic poetry, using his lens to uncover unexpected beauty, rhythm, intensity, and even a quiet melancholy in the mechanization of progress. In what might have been a dry technical record, he finds sacredness in steel, movement in machinery, and an eerie poetry in progress itself, revealing the human and environmental stakes of industrialization as it reshapes both landscapes and lives.

Prespes, Takis Hatzopoulos, 1966, 14΄

“A corner of Greece. Prespes.” So begins the documentary short that Takis Hatzopoulos shot in 1966, the first major act of a journey that would inevitably lead him to Gazoros Serron in 1974 and from there to his time on the TV documentary series Paraskinio, an inexhaustible hothouse of films and filmmaking talent. Hatzopoulos chronicles this one corner of Greece, where a lake divides people into nationalities, in 14 minutes, with obvious echoes not only of the documentation but also of the fiction of Takis Kanellopoulos as it is captured in the black and white photography of Syrakos Danalis, the music of Kostas Mylonas, and the voice-over of Angelos Antonopoulos. The stultifying daily routine, the unvarying days following one after the other, the border that ultimately separates those who remember and those who wait, the hardest hour of the day – nightfall – a circle of life without “the possibility of a surprise,” a “simple world” that says good morning in three languages, becomes through Hatzopoulos’ gaze a small, melancholy ode on the beauty and heartache of a place. It is also a biting commentary on the wider Greece that would dismiss concepts such as tolerance, coexistence, and simplicity, eventually crossing the border and destroying the sacred balance between the insignificant and the significant that is respected only by those who have learned to look at God from the measure of a man.

Thirean Matins, Kostas Sfikas - Stavros Tornes, 1968, 22΄

A “visual social study” on Santorini at a time when the primitive agricultural economy was gradually giving way to the emerging tourist industry. The impoverished and malnourished inhabitants are juxtaposed with the evocative beauty of the island, against a soundscape of chanted matins. Filmed on the island in the summer of 1967, at the beginning of the dictatorship, this short film uses a powerful counterpointing of images and music to go beyond the limits of a simple folklore documentary, presenting a haunting portrait of a two-tier society, an ominous vision of an already spreading future. “Tragic, satirical, epic, lyrical elements had to be blended together within a musical frame completely divested of naturalism, acquiring a musical expression that stems from tradition while also being a present-day anti-metaphysical cry of the suffering,” say the two directors about this hitherto rare and happy cinematic collaboration. The soundscape of the film is thus transformed into a frame of juxtaposition and exposition. Combining this with the unique use of editing and photography, the film takes the viewer on a profound and shocking journey of observation. Ravaged populations, an entire class in the service of the tourist boom, in a cuttingly political precursor of New Greek Cinema, which was to arrive with the restoration of democracy.

Visit Greece, Fotos Lamprinos, 1969, 25΄

Through the exclusive use of newsreels from Soviet archives, Fοtos Lambrinοs embarks on a historical retrospective, spanning from the dictatorship of Metaxas (1936–1941) to the Junta (1967–1974), in one of the most idiosyncratic "documents" of Greek cinema. This is not a historical film in the strict or even the broad sense of the term. Rather, Visit Greece – its title dripping with irony – is a bold satire that verges on an oblique, experimental ethnography. The film comments on and ridicules some of the most tragic moments in Greece’s recent history, as various “tourists” arrive – uninvited and, more often than not, armed – to impose a regime of their choosing. At the close of the 1960s, in the midst of the Colonels’ dictatorship, Lambrinοs leaves his mark on the reinterpretation of Greek-related newsreels, a field to which he dedicated a significant part of his work in collection and archiving. The film delivers a timeless message of resistance, addressing a hospitable country that has paid, and continues to pay, the price of exploitative tourism-driven development.

Kastoria, Takis Kanellopoulos, 1969, 24΄

“And as evening fell, a revelation unfolded within him. He slowly realized that what he was seeking, what he was looking for, the beauty he was searching for, the fairy was the city itself. Kastoria!” The third part of the informal “excursion” to Macedonia – that began with Macedonian Wedding (1960) and continued with Thasos (1961) – Kastoria, with its foreign traveler on horseback seeking a fairy in the modern but rather timeless everyday life of the Macedonian city, closes a perfect cycle of uncompromising documentation right as the curtain rings down on the 1960s. Takis Kanellopoulos has now definitively exchanged history for myth (and its representation), and here he uses it as a bridge between past and present, finally mythologizing a city which, through his gaze, regains anew the characteristics of a rare Greekness, carved from Byzantine ghosts, ancient Greek outbursts, materials of soil and water that are stateless yet deeply rooted in a Greece that remains to be discovered. The film, produced by Giorgos Nasioutzik and awarded Best Short Documentary Film at the 1969 Thessaloniki Film Festival, was the least proprietary of its creator’s works and hard to find – even lost – over the years. It reappeared after a long absence in 2025, not in its original color version, through a network of collectors, providing the opportunity for a comprehensive study on Takis Kanellopoulos’s trilogy, a turning-point for creative documentary in Greece.

The Goat Dance, Pantelis Voulgaris, 1971, 22΄

A strange, muffled emotional charge pervades Pantelis Voulgaris’s Goat Dance, a cornerstone of Greek ethnographic documentary: as we watch, step by step, the preparations for the Skyros Carnival, while the islanders dress up in the bizarre costumes that transform them into terrifying, grotesque creatures, half human and half animal, we feel that order is slowly being disrupted – and so much the better. Carnival is a wild time everywhere – the breakdown of order is, after all, its raison d’être – but in Skyros the feast of misrule seems to preserve something of the ancient, pre-Christian Dionysianism that once flourished in the Greek archipelago. Without verbal commentary, the film records, with wonder and awe, the deviation from the norm in which a whole community briefly indulges, conveying something of the festive yet unsettling atmosphere of a spectacle that unites an entire island.

In Mytiline, Manos Efstratiadis, 1973, 13΄

A unique snapshot of Mytilini in the early 1970s: the camera of Manos Efstratiadis, in constant curious motion, follows the streets of the town, enters shops and houses, records public ceremonies and private gatherings. In just thirteen minutes, the film manages to achieve something impressive: without dialogue, exclusively through its editing and subtle satire, the petty-bourgeois life of the provincial town, the kitschy aesthetics of the Junta, the supposed modernization through tourism, the onslaught of concrete in the commercial alleyways, and the predominance of the Colonels’ “Homeland-Religion-Family” doctrine are thrown into high relief. Thanks to his oblique gaze, In Mytiline cu is watched with a wry smile, bringing to mind echoes of Dionysis Savvopoulos’s song “Paranga” [The Shack]: “Ladies, philanthropic priests, contractors, psalms, and serenades...”. In 1973 the whole of Greece was an “unending shack,” and Manos Efstratiadis’s documentary confirms this.

Megara, Sakis Maniatis - Yorgos Tsemberopoulos, 1974, 72΄

The unbreakable bond between man and his native soil, the way the landscape shapes its inhabitants – and their political awareness – and the importance of localness as a means of resistance lie at the heart of Sakis Maniatis and Yorgos Tsemberopoulos Megara, a film rightly considered one of the most important Greek documentaries of the last fifty years. Filmed at a time when the concept of ecology was non-existent in Greece, Megara follows the struggle of the inhabitants of Megara against the Junta’s decision to expropriate a large area of farmland to build an oil refinery. The last part of the film documents the farmers’ decision to join the students of the Athens Polytechnic in November 1973 following their unjust treatment by the state and the courts. The struggle for survival of the rural people of Megara and their relationship with their land are still strikingly relevant today.

Gazoros Serron, Takis Hatzopoulos, 1974, 77΄

In 1974, shortly before launching the legendary Paraskinio [Backstage] along with Lakis Papastathis, which was to define a new era in Greek TV documentary, Takis Ηatzopoulos visited Gazoros, a small village of tobacco workers in Serres, with “two people, a 16mm camera and a tape recorder.” He was to record more than the everyday life of a place marked by the struggle of making a daily wage, the heartache of emigration, and the ground zero of a whole country in violent transformation. True to his principles that “there is no cinema outside the class struggle” and that “documentary is created, reconstituted, composed in the editing room,” he separates the villagers’ narratives (of which the film exclusively consists) from the images of their daily lives, liberating an incalculable amount of authenticity based on human toil, survival, and the dream of a better life. While it feels as though he is preserving the historical memory of the place, essentially letting the village tell its own story, Hatzopoulos also engages in a timely political commentary on this very need, disrupting the established anthropogeography of the Greek countryside and the concept of poetry as it sneaks into the documentation. The microcosm of Gazoros becomes Greece in miniature, his documentary forming a testimony that is both historical and timeless. Best Production Award, 15th Greek Film Festival, 1974.

On a Little Greek Island, Matheo Yamalakis, 1978, 56΄

“The difference between a computer and people is absurdity”: this phrase, one of the first heard in Matheo Yamalakis’s film, is the key to a documentary that unfolds like a joyful revelation. Yamalakis was a sensitive filmmaker whose oeuvre is still largely unfamiliar to the inquiring viewer. His camera wanders around Ios in the summer of 1976, freely, almost associatively recording aspects of a Greek island perched on the cusp between a traditional, pre-modern world and a sweeping shift in mores. Therein lies the absurd, bitter comicality of this perceptive portrayal of the island’s microsociety, which covers everyone: grotesque local dignitaries, storytelling taverna jokesters, cunning small shopkeepers, naïve tourists, young women crushed by the small-mindedness of provincial life. All are woven together in the most effortless, tenderest way, crafting a kaleidoscopic portrait of the Greek archipelago, timeless in its conception and power.

A Documentary, Nikos Koutelidakis, 1980, 20΄

The literal title of this film by Nikos Koutelidakis, loaded as it is with layers of irony and secondary meaning, serves as an early inkling of what will become overtly apparent right from its opening shots. The camera contemplates the abandoned mansions in the town of Galaxidi, focusing first on the damage done by wear and tear to their exteriors, and then on their vacant interior spaces that once were filled with a human hustle and bustle. The storied past of this place, including details that evoke its former commercial shipping glory, becomes mired inside Galaxidi’s listing around that time as a protected traditional settlement, one that tries to shake off the quaint, nostalgic air imposed upon it by a pivotal decade at its dawn, only to become trapped once more within the guise of the vintage tourist attraction it remains to this day. Without warning, and much as the past intrudes on the present (or much as the imaginary is delineated by the real), Koutelidakis dedicates a ceremony to Galaxidi, a rite of valediction or perhaps of welcome – it makes no difference which. It is the revival of a carnival custom that sweeps you off into a convulsive death ritual before you even get the chance to acclimatize yourself to its beat, setting the tenor of a Dionysian requiem that does not get to complete its melancholy cycle before it folds within it “a documentary” that might well pertain to every place in Greece that watched on as time effaced its defining characteristics, the way rain washes off the paint that adorns the human order, as if in an attempt to reveal its true nature.

Layer of Destruction, Costas Vrettakos, 1980, 32΄

In the late 1970s, a reservoir is built on the River Mornos to supply the capital with water. An entire riverside village, Velouchovo, must be abandoned – a forced destruction that seems like a sacrifice in the name of progress. But there is another sacrifice, too: that of an ancient city that once flourished on the same banks and that now, just as it was beginning to be uncovered by the archaeologists, will be flooded forever. Insightful and elegiac, Costas Vrettakos’ film extends in multiple directions at once: a melancholy record of the decay of a traditional community in the mountains of Phocis and a thoughtful archaeological documentary, Layer of Destruction can also be viewed as a gripping thriller, an archetypal struggle of memory against oblivion, as the excavators fight to save the traces of the ancient city from the water level that rises day by day, swallowing everything in its wake. And if the film perceives History as a palimpsest of destruction, if it comments on indifferent and amoral nature that erodes everything, surrendering all to oblivion, its gaze is not a pessimistic one: it is from the viewer’s questioning of what is worth saving and what is not that the memory of the future will be born.

Fournoi, A Female Society, Alinda Dimitriou - Nikos Kanakis, 1983, 47΄

On the island of Fournoi in Ikaria, a researcher observes the life of the inhabitants. He has no script or questions prepared; he merely observes. The island thus comes to life before our eyes, through its people, through memories, through struggles and daily toil. On the island, men are sailors and women have taken on all the jobs that one would more conventionally expect men to perform, from construction to farm work. Alinda Dimitriou and Nikos Kanakis’s camera captures the relations between the two sexes and how the division of labor is a key gear in the operation of the social machine. With great dedication to oral history methodology, where history is narrated through the experiences of the witnesses themselves – usually with no outlet or voice of their own – Dimitriou and Kanakis perfect a kind of political documentary that does not remain in sterile recording but connects observation with ideology and the social paradigm. Their anthropological gaze provides a roaring platform for voices marginalized by the official history records. The case of Fournoi perfectly points this out, as feminism develops organically, due to the economic and social conditions on the island. The film Fournoi, A Female Story by Alinda Dimitriou and Nikos Kanakis (1983), produced by the Ministry of Culture, was restored and digitalized at the expense of the Ministry of Culture (2021). It was granted for free for its screening at the 27th Thessaloniki Documentary Festival.

Heracles, Acheloos And My Granny, Dimitris Koutsiabasakos, 1997, 29΄

In Armatoliko, a mountain village in Trikala Province, high in the Tzoumerka mountain range, on the banks of the Acheloos, the 89-year-old Mrs Dimitra lives alone. She is the beloved grandmother of director Dimitris Koutsiabasakos, who visits her with a small crew of friends. The result of the visit is Heracles, Acheloos and My Granny, one of the most iconic Greek documentaries of recent decades. Through the unforgettable, laughing, down-to-earth figure of his grandmother, Koutsiabasakos’ lens captures the rugged and indomitable, inexpressibly tender and loving spirit of the Greek countryside, as well as the dark and turbulent history of the 20th century, the wounds of which are inscribed on the old woman’s body. Wounds which not only still gape, but on which new wounds are being piled up, as Armatoliko is shortly to be flooded by the waters of the Acheloos, due to the controversial dam being built in the area. Rarely has a short film captured the spirit of a place, and of a century, so vividly, bursting with emotion and love.

The Dance Of The Horses, Christos Voupouras, 2000, 64΄

In the villages of Lesbos, a land charged with history, ancient pagan customs survive, grafted with the Christian faith and the spirit of the Near East. From Sappho to the present day, this fascinating melting-pot conceals secrets. The Dance of the Horses by Christos Voupouras devises a tender – and ingenious – way to reveal them to us: an eight-year-old boy asks his grandmother with childlike innocence about a strange, cruel custom carried out in honor of Saint Charalambos, and the grandmother – the archetypal grandmother of all – unfolds wonderful and frightening stories, tales of faith and infidelity, like a Scheherazade of the Greek countryside. The dense and complex identity of an island and with it a whole country, as it is carved out of and survives in its ancient rituals, emerges brightly lit before the eyes of the viewer, who, for the 64 minutes of the film, becomes an eight-year-old child in their grandmother’s arms.