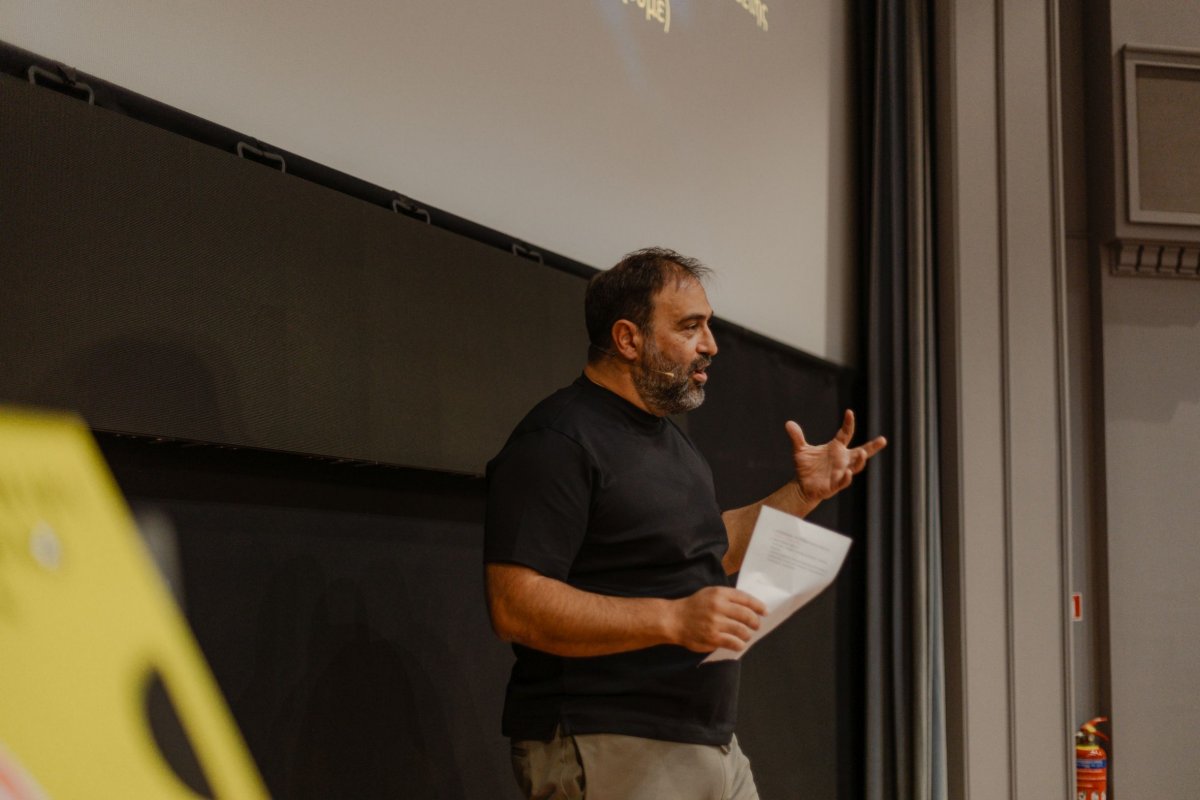

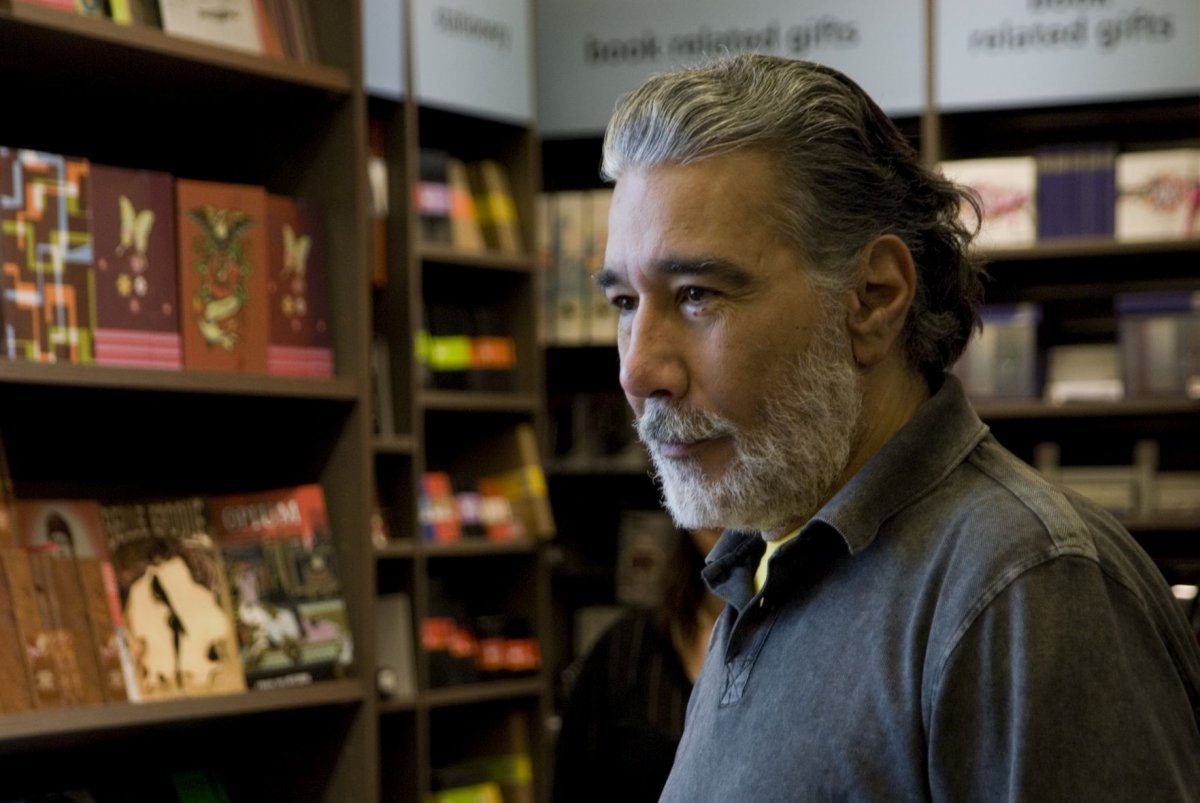

Kostas Christides’ masterclass titled “Scoring a Life between Hollywood and Greece” was held on Tuesday, November 5th, at the packed Pavlos Zannas theater. The event took place within the framework of the Thessaloniki Film Festival’s Meet the Future action, which aims to bring forth the up-and-coming Greek professionals from different branches of the film industry. This year’s Meet the Future foregrounds the art of film scoring through the tribute “Music in Motion: The Art of Film Scoring”, welcoming film composers of the younger generation from Greece. Composer Kostas Christides discussed the process involved in composing film music, as well as the way to render original music an essential element of the narrative. The discussion was moderated by Eleni Mitsiaki, film music consultant.

The masterclass kicked off with a brief introductory video showcasing one of Kostas Christides’ collaborations with Christopher Papakaliatis, in the film Worlds Apart (2015). The composer has created music for various Netflix series, including Benji, Love and Gelato, Baytown Outlaws, Love Happens, Dark Ride, among others, and has also arranged the musical scores in many major film hits, such as Spiderman 3, The Hurricane, Swordfish, Sweet November, The Core, The Exorcism Of Emily Rose, and A Quiet Place: Day One. His partnership with Christopher Papakaliatis continues uninterrupted in the second season of Maestro in Blue, the first television series to be distributed worldwide by Netflix.

Eleni Mitsiaki then thanked the Festival and introduced the acclaimed composer: “We would like to express our gratitude to the Festival for deciding to delve into the essence of film music, for loving film music and organizing a series of masterclasses this year, as well as the Meet the Future action, which is dedicated to film music. I may be a teacher, but I am also a film music aficionado, and I’ve been following Kostas Christides since his time in Los Angeles. I remember once, many years ago, when I was studying in Thessaloniki, I was waiting for the bus in front of a record store, by chance. I could hear the melody from The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci, the masterful music by Ryuichi Sakamoto, emanating from within. I sat and listened, missing three buses in a row. It was at that moment that I realized how pivotal a role music would play in my life,” she added, giving the floor to Kostas Christides.

Kostas Christides thanked the Festival for the hospitality, and the audience for their presence. Immediately afterwards, he recounted his own first first steps in the music industry: “I have been learning the piano since I was a child. I remember my brother giving me as a present the Star Wars’ soundtrack, which I listened to, rather obsessively. Sometime later, I purchased the Indiana Jones soundtrack. It was after six months I realized the composer is one and the same in both cases; John Williams. My entire allowance was spent for such things. I liked the kind of instrumental music that carried a more contemporary sound.”

Next, he talked about his first steps in the United States: “Following the completion of my music studies in London, I moved to Los Angeles in 1997, and enrolled at the University of Southern California to gain a better education on film music. I met Hollywood’s acclaimed composer, Christopher Young, through the classes, and I had the opportunity to collaborate with him. I was essentially his right hand for many years. This experience served as another formidable ‘school’ for me. I worked for him, and alongside him in major projects (Entrapment, Pet Cemetery, among others), ghostwriting, learning a lot about a team’s interactions, as well as the micropolitics defining the relationship between composer and filmmaker. A couple of years later, I started working as a composer and arranger, independently,” he remarked on the subject.

Moving on, he analyzed the components comprising the sound of a film:

The sound recorded in the background during filming.

The sound recorded during filming or the parts of it which are replaced at a subsequent time in a recording studio (ADR).

Original music score (instrumental) and songs. Kostas Christides clarified that the role of a music editor in film has much to do with the songs, and little to do with the original music score.

Unrealistic ambiance / natural sounds simulation.

In response to a question posed by Eleni Mitsiaki on what an emerging composer’s first professional ventures should look like, Kostas Christides answered: “Attending film festivals such as this one and meeting filmmakers is a good way to start off. Always have audacity, yet remain polite. Promote your work gently, without exaggerating. Always keep in mind that an esteemed professional won’t probably be hearing each demo you send. So, approach new filmmakers embarking on their first endeavors, especially for short films. Get in contact with filmmakers because if they make it, they will most likely pull you with them. From the get go, work on making the music sync with the film: the art of film music is multilayered. Your music must be in line with the director’s instructions, and of course, you must do all these within the constraints of specific time frames. Leave your ‘ego’ outside the recording booth. Realize you are part of a bigger team serving the vision of the director, the project’s leader. Translate, as far as possible, the director’s words into music. More often than not directors lack musical skills, and as such you must play the role of a translator, as well. If a director tells you he wants something blue, you should manage it somehow! When composing film music, one does not simply write music, they are assisting the art of dramaturgy.”

On the first actions a professional composer should take, prior to composing, he stated: “Personally, I avoid composing with only the script at hand. It's like those people that claim to like the book better than the movie. Consider the creative freedom a book affords you! You comfortably read it at your own time. A film is much more limited. There is always the risk of liking the script more than the final result. I always use the film as a source of inspiration; faces and colors are a big help to me. I watch it several times, over and over again.” At this point, Kostas Christides demonstrated on screen the format of a real script, informing the audience that a page usually equals one minute of action approximately, which allows professionals to roughly estimate the duration of the film.

Then, he touched upon another important concept for professional composers: temporary music score: “This is a music score composed of already existing scores and it is a practice that is done solely for aesthetic and practical purposes. The music editor is responsible for this. It is done alongside the editing process of a film. It can be a composer’s best ally, or his originality’s downfall. Temp score is helpful for me as it sets the tempo. There is a danger that the director will get used to it because he’ll be hearing it constantly, and end up asking for something similar in the long run for the final product. When such a thing happens, I advise my director to take a break from listening to any music at all for two days, and then go back into the editing studio - give my music a chance to win him or her over,” he explained. He also emphasized how important a music editor is, adding that they are the composer’s primary ally within the editing room.

Then, Kostas Christides continued on, analyzing the spotting session, a key point in the process of composing film music. This refers to a meeting between the composer and the filmmaker, the producers, and the music editor so as to discuss the following:

- The style of the music score and the orchestration, taking into account the budget.

- Music’s starting and ending point in each scene, within the constraints of timecodes (the use of which follow a complex time marking that is divided into twenty minutes, originating from the days of the film reel).

- The composer’s approach.

- The themes; the number and type of music "themes" that will be included.

- The delivery plan, which is always defined by strict deadlines.

“This session is evidently extremely significant. I like to imagine that during this meeting a train is placed on the rails, and we are getting ready to move onto the next stop,” he noted.

Then, he displayed some screenshots from the special sound organization and editing programs a composer uses, such as CueDB. He advised emerging composers to record each and every idea that comes to mind, as it may prove useful in the long run. He highlighted how important it is for a composer to respect the dialogue in a film and avoid overshadowing it with music. He also stressed the importance of not overloading the film with music, saying in particular: “Putting an overwhelming amount of music in your films is akin to moving next to an airport. After five days, you will no longer hear the planes.” He listed three examples of ingenuity in the less is more approach to music in contemporary American cinema: Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan, Robert Zemeckis' Cast Away, and M. Night Shyamalan's Signs.

Next, referring to his collaboration with Christopher Papakaliatis, he mentioned: “I contacted Cristopher myself after watching If. He hadn’t heard of me and asked me to send him some music samples. I lied about having no access to my files at that moment in order to gain time. Within 24 hours, I had watched all of his series on YouTube, detecting his love for the piano and the violin. That was how I got the job!” Then, Kostas Christides showed the audience a series of snippets from Maestro in Blue’s episodes, a scene from Benji, as well as one from Spiderman 3.

Concluding, in response to a question about how much things have changed in film music composition compared to previous decades, he stated: “I think nowadays you have greater access to information. Simultaneously, you have a whole lot of competition, but also a lot more content in need of soundtracks. Avoid being too antagonistic: collaborate with each other and be generous with your knowledge. Remember to get out of your comfort zone. Be informed, have audacity, always politely, don’t be overly selfish, and forge your own path. The most important thing is to reach the age of 80, stare at yourself in the mirror, and be sure that you had fun along the way.”