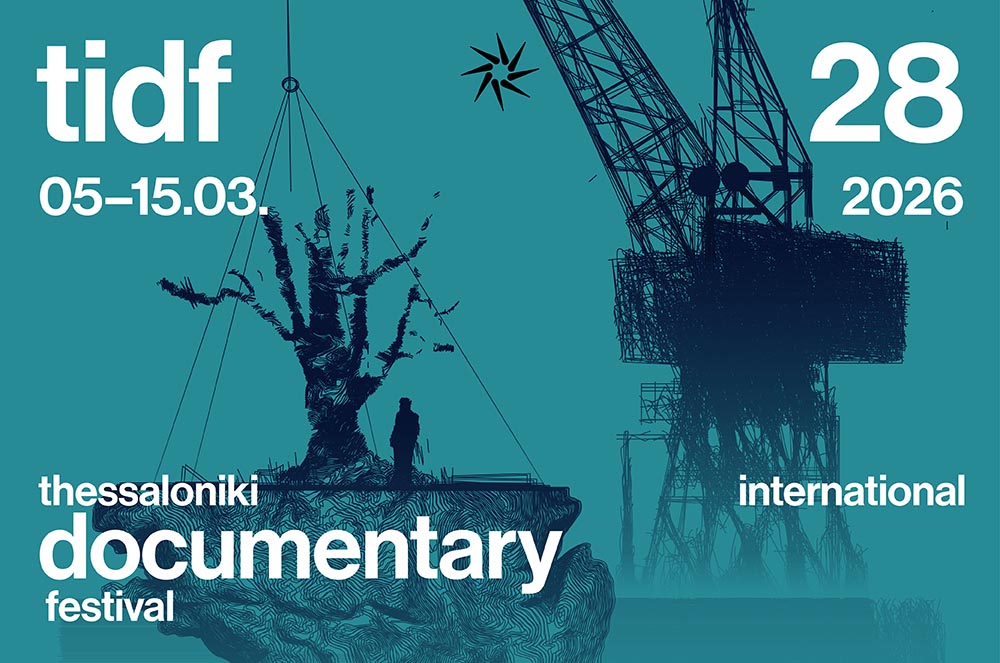

The screening of the film Only on Earth took place on Saturday, March 15, at the Pavlos Zannas Theater, in collaboration with the Heinrich Böll Foundation, and in the presence of the film’s director, Robin Petré, as part of the 27th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival. The film takes us to southern Galicia, one of the most vulnerable regions in Europe to the threat of wildfires, capturing both the harsh beauty and fragile balance of the natural world. During the hottest summer ever recorded, relentless flames devour everything in their path, while people and animals alike fight for survival. Wild horses, which have roamed the Galician mountains for centuries, play a vital role in preventing wildfires, reducing the vegetation that can serve as fuel for the flames. Yet, their declining population brings to light the growing clash between human activity and nature. Following the screening, a discussion was held with the participation of Michalis Goudis, Director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation (Thessaloniki office, Greece), which supported the event, director Robin Petré, and photographer Ilir Tsouko.

The Heinrich Böll Foundation recently supported a project titled Beyond Destruction, focusing on regions devastated by natural disasters during the summer of 2023. Photographer Ilir Tsouko and writer Anja Trollenberg traveled across Rhodes, Thessaly, and Evros just a few months after the catastrophe, documenting both despair and hope, the hardships and resilience of people and their communities, drawing a subtle connection between these stories and the climate crisis affecting the entire planet. Beyond Destruction is a story of survival, of community, and of the unyielding human spirit.

The event was introduced by Yorgos Krassakopoulos, Head of Programming of the Festival, who welcomed the audience and noted: “We are delighted to collaborate once again with the Heinrich Böll Foundation to present a film that speaks to a crucial and urgent issue that concerns us all. After the screening, a discussion will follow, in the presence of the film’s director, Robin Petré.” Michalis Goudis then took the floor: “We are pleased to be joined by director Robin Petré, photographer Ilir Tsouko, and beekeeper Giorgos Karafyllidis from Evros, who will each offer a different perspective on the broader issue of the climate crisis. We will talk about how humans intervene in the natural environment, what happens when our actions trigger extreme phenomena, and, finally, how we can move forward after destruction.”

Following the screening, an extensive Q&A session took place. Robin Petré opened the discussion, noting: “I am primarily interested in the relationships between humans and animals, and in how nature is constantly changing around us, a change that calls for a redefinition of our relationship with it. This transformation is happening all over the world, both in Spain, where I come from, and in many other countries. Only on Earth is part of this ongoing exploration I’ve been pursuing in my recent films, approaching these questions from different perspectives and focusing on different issues in various countries. I grew up in a small village on the edge of a national park in Denmark, surrounded by both domestic and wild animals, something that has shaped me profoundly. The natural world was one of the most precious parts of my life as a child and as a young woman. Over the years, I’ve realized how much nature has changed, even in the place where I grew up. I personally believe there is something fundamentally wrong in the way we alter the natural landscape and destroy natural habitats. We are pushing biodiversity to dangerous limits, creating immense problems not only for wildlife but also for ourselves. This is one of the central themes the film seeks to address,” the director remarked.

Speaking about her experience in Galicia, where the film was shot, Robin Petré shared: “I have only been to Galicia for the making of this film, so my first time there was in 2021. During that time, I made many friends, trying to understand the region and the way people live. I spent time observing the mountains where the wild horses live, mountains that are now covered with wind turbines. The new roads built for the installation and maintenance of the wind farms are making life more difficult for the wild animals, especially the horses, as they bring people to areas that were previously untouched. This situation has led to a sharp decline in the population of wild horses, which play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of the local ecosystem. These wild horses are the only animals that eat a specific native thorny bush in Galicia, a plant that can grow up to four meters high and poses a severe fire hazard. The horses have adapted over centuries to feed on this particular bush, and if it is left untouched, it can overrun entire mountains,” she noted.

The director also spoke about the challenges of filming in the midst of wildfires: “One of the biggest challenges we faced was the unpredictability of the fires. Galicia is an enormous region. Often, we had to drive for two hours to reach a wildfire, only to realize that we couldn’t get close because of police roadblocks, which meant we couldn’t shoot any footage. On our way back, we were constantly on the lookout for fires we could actually approach. To do that, we needed to form strong friendships and relationships with local firefighters. Having an experienced firefighter by our side, someone who could read and predict the direction and intensity of a fire, was absolutely invaluable. These wildfires are extremely dangerous and move at terrifying speed. We also faced serious issues with our equipment. Our camera partially melted and had to be replaced. A fire truck ran over one of our tripods, and at three in the morning, we had to make superhuman efforts to save the footage we had managed to capture,” Petré recalled.

“Beyond the technical challenges, the aesthetic of the film was equally important to me and my cinematographer,” Robin Petré continued. “I wanted to use wide-angle lenses that would allow me to fully immerse the audience in the experience. We shot the scenes using 28mm and 35mm lenses, literally standing right next to the firefighters. This approach, as opposed to using a zoom from a distance, creates a completely different feeling, something I was determined to capture in the film. The same applied to the scenes with the horses. We were inside the herd, sometimes as close as fifty centimeters away from the animals. It took countless takes and retries, because a single mistake could have destroyed the camera. But it was essential to achieve this sense of closeness and immediacy, to convey the intensity and the urgency, what it really feels like to be inside a herd of wild horses surrounded by fire. As for how I felt at that moment, it’s hard to put into words. I was so focused on my work, on the frame, on timing, on movement, that I didn’t have time to process my emotions. I was there as a director, trying to make the film work. All my skill and attention were dedicated to surviving and to completing the film,” she added.

At that point, photographer Ilir Tsouko took the floor: “Watching the scenes in the film, I was mentally transported back to my visits to Alexandroupoli, Larissa, and Rhodes. I vividly remember the interviews we conducted in those places, the way people described their experiences gave off a sense of an unhealed wound. Through our work, we realized that disasters mark a turning point in people’s lives. It’s as if there’s a dividing line. Their lives are split into before and after the disaster. Before, they lead an ordinary life, never imagining how things could change. They don’t wake up in the morning wondering if there will be a tomorrow. Nature is constantly changing, and we now stand at a critical juncture, facing two parallel challenges: how to bend the course of this progression, and how to deal with the aftermath, how to learn, as a society, to manage the day after more effectively,” he noted.

"Anja Trollenberg and I decided we had to do something. We had seen the scenes of devastation on the news, but we wanted to understand how people face life after the disaster, six months later. We presented our idea to the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Thessaloniki, and they supported us. So, we traveled across Greece, gathering photographs, videos, and stories. All these experiences were brought together in a book. The question that kept coming back to us was: what comes next?" he said, referring to the Beyond Destruction project.

Speaking about the hope that follows such devastation, Ilir Tsouko added: "After a disaster, two parallel processes begin. One is political, we discuss infrastructure, new roads, and how to rebuild the destroyed areas. The other is social, about people and their relationships. Before the disaster, we may not have had good relationships with our neighbors. But afterward, your neighbor becomes the closest person to you because you share the same struggle. Disasters bring us closer and remind us that what makes us human is solidarity and hope.” "I remember a woman in Alexandroupoli, over 80 years old, whose home had burned down. Her cousin gave her another house nearby. Even though her house was gone, the garden in front of it remained untouched. Every morning, she watered the flowers. When I asked her why she did that, she said: 'Because there is still something beautiful here that gives me hope. Who knows, maybe future generations will rebuild the house, and the flowers will already be here.' In moments like these, hope gives us the strength to face the unimaginable. Destruction is not something you can erase with an antibiotic. It’s something that stays with you. That’s why solidarity and hope are the strongest tools we have.”

Next, one of the protagonists of the Beyond Destruction project, Giorgos Karafyllidis, took the floor, initially referring to the wildfire in Evros: “We experienced the greatest disaster ever recorded on European soil. A total of 936,000 square meters were burned, an area that represents 65% of the entire Evros region. It was, without a doubt, an unimaginable catastrophe. I tried to stop it, I was there myself, fighting the flames, helping others. At the same time, I knew I couldn’t stop it because of climate change. Today, the forest shows some signs of revival and recovery. However, the risk of wildfire will always be present. This is why I always emphasize the need for bees in a forest. Scientists have estimated that without bees, there would be no life left on the planet in just four years! As bees fly from flower to flower, they enable pollination. Without them, there would be no endless cycle of nature’s regeneration.”

Speaking about how life continues after the fire that destroyed his beehives, Karafyllidis said: “In terms of honey production, I am now forced to travel over 400 kilometers to reach Drama and Nevrokopi. Regarding the forest’s recovery, for the past two years, all beekeepers have been leaving 40 to 50 hives in the forest to help restore its fertility.” He also added that a video he shared on social media, showing his burned beehives, helped raise public awareness around the issue of wildfires.

Speaking about the presence of wind turbines in her film, Robin Petré noted: “As shown in the film, wind turbines have been installed in ways that harm animals, plants, and the environment. They also represent human interference in nature through urbanization and monocultures. The film highlights that these changes are driven by profit, often overlooking the consequences for the natural world. While green energy is essential, the film raises the question of how it is implemented: is it done with profit as the ultimate goal, or with respect for nature and local communities? When profit is prioritized, new problems arise, such as the disappearance of wild horses, a species whose absence further exacerbates wildfires. So, respect for nature is fundamental to any truly sustainable development.”